From The Abstract To Concrete

Although winter holds no great charm for many of us in this northern land, a frigid day near High Park may still offer unusual and evocative aerial images.

And perhaps they will set our minds a-puzzling, for winter often does that when viewed from a height, inviting us to wonder, what exactly am I looking at?

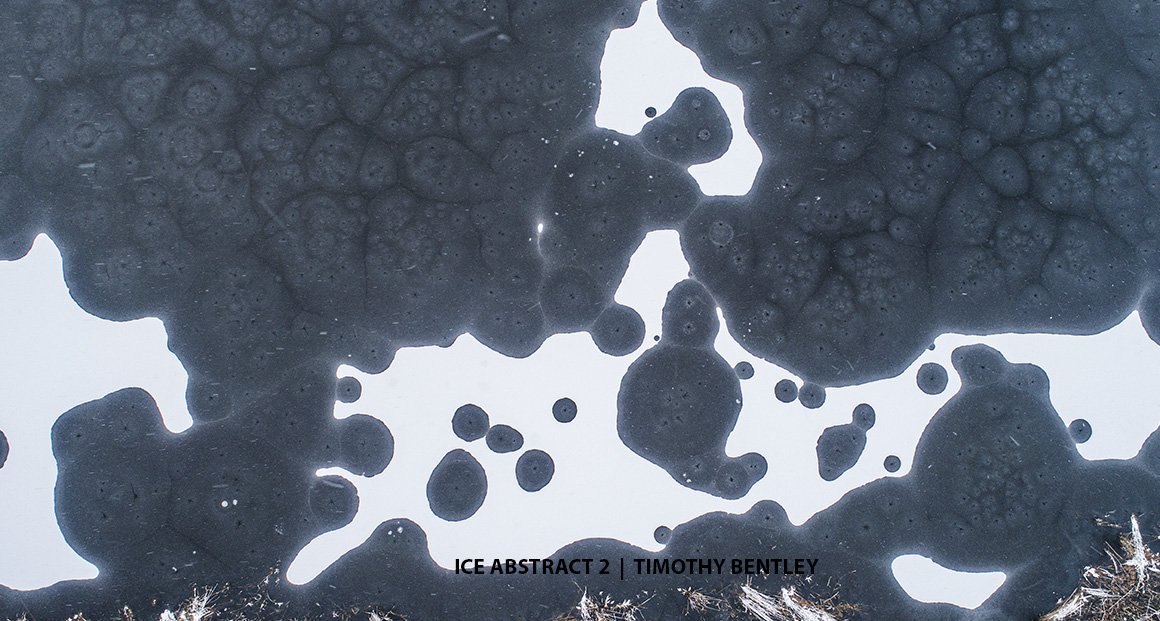

Take this abstract image of the ice on Grenadier Pond.

It welcomes speculation. What does it represent? Were holes drilled in the white patches by some unearthly machine?

Is the middle portion, with its rippled grey matter, perhaps the outer surface of a maritime brain?

And is that a dreamy, filmy negligee hovering at the edge? Such questions are the territory of the abstract.

As a photographer, my mind goes back and forth about what makes an abstract image most effective. Part of me issues a strict demand: eliminate the dark liquid water on the right. Crop out any external reference. Let the abstract patterns of the ice stand by themselves.

Another part of my mind argues the opposite: to display the context superimposes a layer of factual interest on top of the layer of pure intrigue.

Is there a right answer?

By the way, the short streaks in the image are not cracks in the ice, but snow driven past the drone by the wind.

Here’s another example from that day.

It would have been no trouble to crop this image, to remove the plants along the shoreline. To do so would certainly invite the question, what are we looking at here? But I decided it was more intriguing to include them.

Yes, the overall impression of the photograph is still abstract. But the context at the bottom of the frame anchors it in reality. Perhaps, it whispers to the viewer, you too could stand at the edge of a winter pond and there discover a beautiful abstraction.

One of the things I most appreciate about winter photography is the muted tonal range - almost black and white, with just a occasional hint of colour.

A few minutes later, I flew the drone east across the water, and spotted the circle on the far shore, where in other seasons multi-coloured flowers surround a giant maple leaf.

With the camera suspended directly above, the light snowfall has obscured and simplified the details of the landscape. Yet, like a subtle engraving, the leaf is still perceptible.

Because of the wide angle lens, the trees that frame the circle appear to lean outwards, away from the centre. Again, winter may have simplified our vision, but here there’s plenty of context on display here.

A couple of weeks before the snowfall, I explored this context dilemma on a visit to the lower reaches of the Humber River.

After I manouevred the drone to a weir, hovering a few feet above the surface of the river, I took a number of shots that, although not abstract, embraced simplicity.

In this, we see the quilting together of three liquid textures: the placid water above the dam, the bubbling foam as it crashes down, and the turbulence as it races away. It’s a rounded pattern that’s effective in its own right.

But there’s no context, no sign of shoreline. So maybe I prefer this image, similar in design, that reveals more of the location.

Does displaying the context make an interesting image even more accessible? I wonder which you prefer.

While I was at the river that day, I also look photographs of the handsome Old Mill Road bridge that crosses the Humber. Those images, by contrast, were quite literal.

This structure was built just over a century ago, in 1916, its arches made of solid concrete faced with stone. When I arrived, it carried only a solitary cyclist, his blue jacket a vibrant contrast with the neutral tones everywhere else.

Whoops, I’d better stop right now. I’ve just realized that in a few paragraphs I have moved from cogitating about the abstract to portraying literal concrete. How did that ever happen?

Return to Blog Main Page

If you enjoyed this, please share this link with anyone who might appreciate a new perspective on our world: TimothyBentley.Photography/Blog

You can visit my pages at 500PX.