Adventure/Misadventure

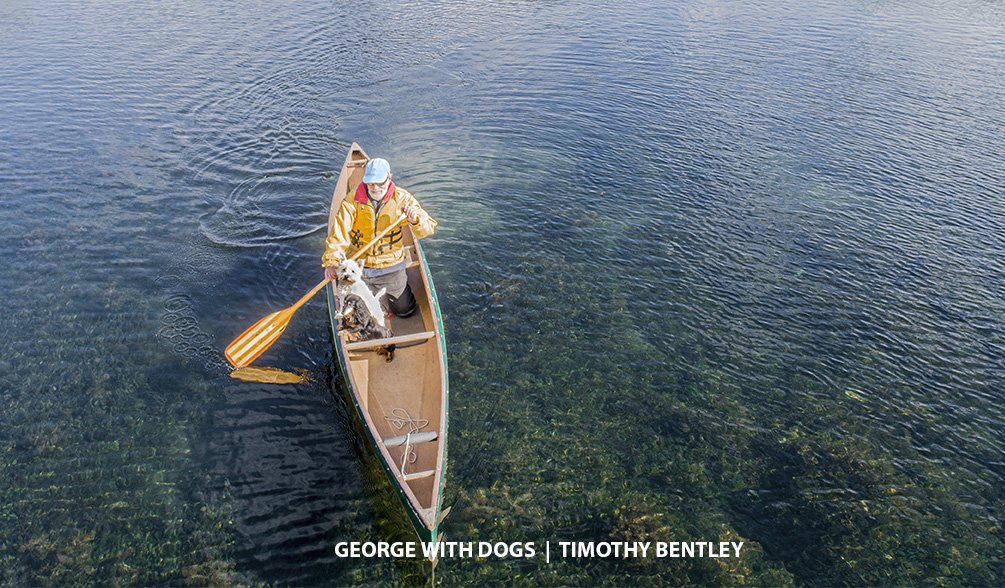

I’ve been looking forward to shooting a second series of aerial photographs with George Caesar, a close friend and extraordinary canoeist.

Last week, we agreed to meet near the high sand cliffs of Scarborough Bluffs.

The day started out really well. George launched his canoe and helped his friends Kate (the white one) and Abby (the dark one) climb on board. They were eager, I was eager, and the winds were calm. The drone took off flawlessly.

What could possibly go wrong?

As George paddled across the lagoon, the dogs stared at the amusing machine hovering over them.

Higher up, a dozen excited gulls flashed and slashed their way through the still air.

Seeing the invisible

A delightful aspect of drone photography is that it often reveals details not visible from ground level.

A couple of years ago, I took a photograph of a stand of trees next to a stream. It was only when I inspected the image more closely that I discovered, concealed in the woods near where I’d been standing, two lovely deer grazing on tender shoots.

Now, as George navigated the narrow passage to Lake Ontario, I saw on the display of my remote control something invisible to him at water level.

A school of carp were racing ahead, trying to escape the canoe, their shadows dark on the bottom of the shallow passage.

In that astonishing moment, I was able to capture only a single fleeting photograph before they raced out of view.

(Drone technology is currently being used in Australia and the US in much the same way, to spot sharks that might endanger swimmers.)

Adventure

As George paddled further into the lake to go round a peninsula that stood between him and the cliffs, I walked the more direct route overland, guiding the drone with the remote control.

In the final aerial photograph I took that day, the canoe and its occupants had shrunk to a tiny spot surrounded by an enormous body of water, beneath the sun and the glorious clouds.

The image was remarkable, delightful, awe-inspiring.

It exemplified another remarkable aspect of drone photography. It allows us to take pictures from locations that the photographer could never physically reach.

But that ability can bring it own challenges.

Misadventure

That’s when something went seriously wrong. As the drone hovered over the lake, it abruptly lost contact with the remote control (RC) in my hands.

The RC could no longer update vital information, like the drone’s location, height, speed. Worse still, I could no longer control the drone. I hunched over the RC, trying to figure out what to do next.

When I looked up again, the drone had disappeared.

To add to the problem, the RC stopped showing me what the drone’s camera was seeing. So it was impossible to use its display to figure out where the drone was located.

I was engulfed in panic.

Just when I thought nothing worse could happen, the RC emitted a low-battery warning.

It told me that, after nearly a half-hour of flight, the drone would soon land itself automatically. Most likely, it would descend to the lake and sink like a stone.

I tried everything I could think of, clambering recklessly over large rocks to reach a higher point from which I might regain contact, but nothing worked.

In desperation, I programmed in a new landing point – near the cliffs where I was standing.

But there was no response, the drone didn’t appear, the RC provided no information, and I was forced to give up.

A few moments later, George paddled up to me. I told him what had happened, and apologized for the failure. I decided to snap a few photographs with my Lumix camera from ground level.

At least I could photograph him canoeing next to those spectacular cliffs.

Then George and I went on an overland search. Just in case.

After an hour, we realized that the drone was not to be found. We concluded that it had indeed dropped into Lake Ontario and sunk to the bottom.

Tired and despondent, we parted, heading back to our respective homes.

Confusion

However, once I got home, things turned more positive. I managed to view a record of the drone’s last movements.

The final sequence, only a few seconds long, surprised and confused me. It showed the drone moving over land, not water. So maybe it didn’t drown.

It seemed that the drone was flying from the location where I had originally launched it, in the direction of the cliffs where I had been waiting for it.

During those few seconds, its altitude was steadily decreasing. And then there was nothing.

Another search

Buoyed up by that information, I returned the next day, to make a ground search of the area where the drone had apparently flown.

At this point, I was prepared to accept whatever damage might show up – broken propellers, bent legs, scratches, even irreparable harm – if only I could retrieve the memory card holding those precious photographs.

I searched the lawns, bushwhacked through the woods, and peered up into the branches of every tree, in case the drone was caught up there. And saw nothing.

I was on the verge of giving up and going home, when I spotted a maintenance crew, and asked if they had seen my drone. To my great comfort, their supervisor opened a closet in his office and handed the drone to me, totally unharmed.

If you heard a loud sigh of relief echoing through the universe that day, it was me.

My best guesses

How did all this happen? I don’t really know, so what follows is pure speculation.

Although the RC is designed to have a long range (7 kilometres), I’ve noticed that local conditions sometimes limit its scope.

When those conditions somehow interrupted the drone’s contact with the RC, it was programmed to return automatically to its original takeoff point. That would explain why it disappeared from my sight, over the lake.

It’s also possible that the RC failed, for a few days later I noticed that its battery wasn’t holding a charge properly. I had to have it replaced.

Either way, when the drone got back to the takeoff point, it must have hovered in the air, waiting for further instructions.

And when I entered the new landing point near the cliffs, that signal somehow did reach the drone. It responded by trying to fly cross-country toward the cliffs and me.

But after all that time aloft, its battery was almost flat.

So it sank lower and lower, until it managed to land safely on a patch of grass. That’s where the maintenance crew discovered it.

The artist and the pilot

Is there a lesson in this for me, and drone photographers generally?

I think it is that we must always resist the temptation to let the artist within, who will do almost anything in search of the perfect photograph, overrule the pilot within, who is responsible for flying the drone without danger to itself or others.

That’s the moral of the story, but there’s also gratitude.

I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity to fly a drone at low altitudes, and sometimes take an extraordinary photograph like the canoe chasing a school of carp.

Return to Blog Main Page

If you enjoyed this, please share this link with anyone who might appreciate a new perspective on our world: TimothyBentley.Photography/Blog

You can visit my pages at 500PX.