The Sailboat From A Drone’s-eye View

To capture an Image of a boat in full sail is challenging at the best of times. The photographer has to cope with the movement of the boat, a different movement of the camera platform, and the constantly changing relationship between them.

But to fly the drone at the same time from on board the sailboat, at the same time, is even more of a challenge.

Let me tell you how my technique evolved.

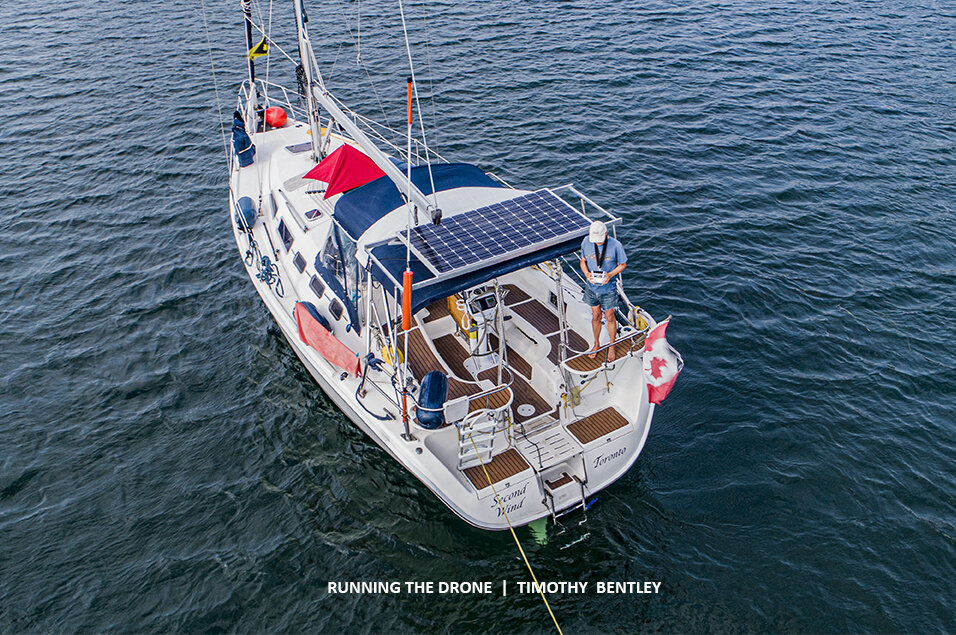

Here, Second Wind is looking pretty off the Mimico shore last summer, pushed along by a southwest wind. We’ve just left the Mimico Cruising Club, where Esther and I keep the boat. On this occasion, Second Wind is towing our dinghy (although most of the time we pull it up on davits).

The drone is high enough to capture most of the deck and the top of the cockpit, while still including the condo towers across the water in the image.

Those highrises are just a hint of the immense vertical town that has sprouted in the past decade or so, in the west end of Toronto. They’ve become home to many thousands of people from all over the world, drawn by the abundant lake vistas, parks, trees, and wonderful shoreline trails.

Flying the drone to take a photograph like this, is an evolving skill.

The first time I flew the aircraft over water, I was terrified, fearful of losing it under the waves. With Second Wind docked at the Prince Edward Yacht Club, Esther and I took the dinghy out, cautiously tied up to a buoy, and I hand-launched the drone.

Having taken some lovely photographs of the bay and town, I directed the drone to the dinghy, took a deep breath, caught the drone in my hand, and exhaled—a deep sigh of relief.

In the months that followed, I kept flying, mainly over the St. Lawrence River around the Thousand Islands. As the drone proved its reliability, my anxiety diminished, and I began to experiment.

I discovered that the flat solar panel at the back of our boat is the ideal takeoff pad, with the boom tied out of the way to port, allowing the drone to take off cleanly. Standing on the aft seat to starboard, I can maintain a clear view of the drone, wherever it flies to.

During takeoff, it’s still uncomfortably close to the shrouds and halyards, so as soon as it has risen a little higher than my head, I direct it over me, past the stern above the water, where there’s no danger from ropes or cables. From there, it can go anywhere I choose.

This image was taken while at anchor off Camelot Island. I photograph most of my Thousand Island images at anchor like this, with Second Wind providing a stable platform, moving only a little with the swells.

Crucially, the boat stays more or less in the same spot. So when I press “Go Home” on the remote controller, the drone will ascend to a safe 40 metres, return to a spot directly overhead, and descend. I will stop the descent when it’s near the water, fly it to within reach of my outstretched hand, and grab it out of the sky.

I don’t land it on the solar panel because there’s always the risk that the boat will swing unexpectedly on the anchor and the spinning props might foul on the rigging.

Back at the city, photographing the boat in motion, I got some support from the drone’s software. Once it was launched from the solar panel, I set up its object recognition function to follow Second Wind from a preset distance. Then I adjusted its altitude to incorporate boat, lake, sky, and city in the shot.

I particularly like how the mast parallels the CN tower in this image, and even on the wavy lake I can see an appealing reflection of the white hull and sails.

By now, it’s late in the afternoon, and the sun is descending. I’ve reset the software, so the drone is now locked in place ahead of the moving boat. It’s flying just above the height of the mast, so that if the software should fail me, the drone won’t collide with the mast.

I like how the jib is illuminated now by the sun behind it, two of the spreaders on the mast casting their shadows. A broad swath of sparkles shines across the water.

It’s a nice ending to an exciting flight. With a couple of dozen photographs in memory, it’s time to recapture the drone.

If I were to press “Go Home” on this occasion, it would attempt to land where it took off, a couple of kilometres behind us. That’s a landing platform much too wet.

So I release the software, steer the drone off to one side, and let the boat pass by it. Then I move it laterally till it’s directly behind us, and very cautiously drive it forward to catch up with Second Wind.

Now I have to act with some urgency. I have to make quick adjustments to change its altitude and location relative to me, without having it drop back. The moment it’s aligned with my position, my arm shoots out and I grab one leg of the drone.

At once, the props start to whine angrily, protesting their captivity, fighting my grip, until I’m able to use my other hand on the remote controller to cut their power.

As I carry the aircraft back on board, I breathe a sigh of relief, even after several years of experience over water. Now I can fully relax.

The drone has safely landed at this moving target, and I can begin to examine its treasure, awakening photographs that sleep in its memory.